|

KEY |

|

Topic |

|

CONTINENT |

|

Town |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

EUROPE |

|

|

|

AFRICA |

|

|

|

|

|

ASIA |

HISTORY TOP

In 711, the Berber landed at Gibraltar. By the end of their campaign most of the

Iberian Peninsula (except for small areas in the north-west such as Asturias and

the Basque) were brought under Islamic rule. The disintegration of the Caliphate

saw Islamic control of Spain gradually eroded by the Spanish Reconquista (Reconquest)

by which the Catholic Kingdoms of northern Spain eventually succeeded in re-conquering

the Muslim states. So, Spain saw on-and-off warfare for almost 800 years .

Moriscos (Spanish ""Little Moors") or Mouriscos (Portuguese) were Spanish Muslims who converted to Catholicism during the Reconquista and later was the sarcastic term for those thought to have outwardly converted while secretly continuing to practice Islam. It also followed Taqiyya, Arabic for caution,. a legal dispensation allowing Muslims to deny his or her faith or commit otherwise illegal or blasphemous acts when in danger of losing life, limb, or property and lived under

From Author's Note in the

'The Hand of Fatima' by Ildefonso Falcones

The history of the Morisco community in Spain, from the conquest of Granada by the Catholic monarchs to their final expulsion, is one of the many episodes of xenophobia in our history. Other examples include Almanzors attacks on Jews and Christians and the expulsion of the Jews by the Catholic monarchs. The conditions for the surrender of Granada established very generous terms for the Muslims. They were allowed to keep their language, religion, customs, properties and authorities; eight years later, however, Cardinal Cisneros imposed the forced conversion of the Moriscos, as well as the elimination of their culture, the establishment of new, onerous taxes, and the curtailment of their administrative autonomy. The so-called ‘new Christians’ became increasingly exploited and reviled, while their previous rights were severely restricted.

The Morisco revolt in the rugged, beautiful region of the Alpujarra was a direct consequence of that peoples constantly deteriorating situation. We know about it thanks to two detailed accounts by the chroniclers Luis de Marmol Carvajal (Historia del rebelion y castigo de los Moriscos del reino de Granada) and Diego Hurtado de Mendoza (Guerra de Granada hecha por el Rey de Espana Don Felipe II contra los Moriscos de aquel reino, sus rebeldes: historia escrito en cuatro libros). This was a war that both sides pursued with the utmost cruelty, although the atrocities committed by the Moriscos are better known, owing to the incomplete nature of the Christian accounts. In spite of this, one of the few voices raised to explain, though not to justify, these excesses was that of the Spanish ambassador in Paris, who, in the letter quoted on page 18, related how an entire village was complaining that its women were raped by the priest, and that their children were born with the stigma of his blue eyes - as is the case of the protagonist of this novel. However, the Christian side also committed atrocities. Massacres (the worst example of which took place in the village of Galera), the forced enslavement of the defeated Moriscos and extensive pillaging were common. For this reason we should give credence to events such as the deaths of more than a thousand women and children in the square at Juviles, and the sale of a similar number of both groups at public auction in Granada, as related in these chronicles.

This butchery was carried out by soldiers and commanders who were not part of the regular forces, and whose sole aim seems to have been personal enrichment. The chronicles constantly give prominence to the efforts to win spoils and share them out, to ambition being the only strategy, and to desertion by men satisfied with the booty they had accumulated.

Together with this, I have also tried in my novel to present an image of the conflicts and conditions within the rebel camp until the Moriscos, abandoned to their fate by Algiers and the Turks (as they had been before and would be again), were defeated by the professional Spanish soldiers. The taking of hashish to instil courage, the use of aconite as a poison on arrow tips, the arrogant attitude of the squad of janissaries sent from Algiers, the corsairs and the inclination some of them had for young boys: all this appears in the books of the chroniclers of the time. Also, in the work Mahoma by Juan Vernet, it is noted that according to Arab legend, several of the Prophet's swords reached al-Andalus, as I describe in my novel.

The Alpujarra uprising ended with the deportation of the Moriscos of Granada to other kingdoms in Spain. In the case of those taken to Cordoba, like the protagonists of the novel, their exodus led to the death along the way of a seventh of those expelled, as seen from the study Los Moriscos en tierra de Cdrdoba by Juan Aranda Doncel.

The defeat, the dispersal of the Moriscos, the discriminatory laws (which also had the result of rendering useless any attempts at assimilation) did not resolve the problem. There are many reports and opinions from the time which not only made this clear, but proposed terrifying ‘final solutions’. As a consequence, there were also many plots, all of which failed. Among the most serious was the one at Toga, which is recounted in the novel and which was thwarted as a result of the documents the King of England sent to the Spanish monarch following Elizabeth I’s death and the Anglo- Spanish treaty. In his book The Moriscos of Spain: Their Conversion and Expulsion, the historian Henry Charles Lea states that 'the 120,000 ducats the Morisco community promised to pay on that occasion to secure the support of the French King for the insurrection were in fact handed over in Fau'; while Dominguez Ortiz and Bernard Vincent, in their Historia de los Moriscos; vida y tragedia de una minoria, maintain that this never in fact happened. However, the payment, or the offer to make it, does seem to be true. For plot purposes, I have decided the payment was made, and have fictitiously put this down to the profits made from counterfeiting money - a real economic scourge which occurred above all in the kingdom of Valencia, where in 1613 the municipal treasury was bankrupted, leading to the withdrawal of hundreds of thousands of fake ducat coins. The Moriscos were directly accused of this counterfeiting. Several Berbers were present at Toga, but the aid was not meant to come from Algiers or the Sublime Porte, but from Christians.

The sufferings that the children went through - and here I am referring to the Morisco children, innocent victims of their people’s tragedy - merit an in-depth study. There is a wealth of references for this: first and foremost, there is proof of the slavery into which children under eleven were forced during the Alpujarra uprising, despite the royal edicts. From our viewpoint, it is also hard to consider all those over eleven as being adult. In second place, once the war had finished, there was the handover of the children of deported Moriscos to Christian families; there are documents that confirm legal processes in favour of these children who were trying to recover their freedom once they reached the age of majority. Third, there was a fresh enslavement of children after the rebellions in the Valencian mountains (Vail de Laguar and Muela de Cortes). Finally, there exists documentation on those children aged under six who were kept in Spain when the definitive expulsion of the Moriscos took place. There are accounts that some families managed to send these children to France (the prohibition was on sending them to Barbary) and that others succeeded in getting round the royal decree by setting sail for Christian countries and then changing course at sea for the African coast. In the novel, several hundred of these children are said to have been detained in Seville. In Valencia, almost a thousand of them were handed over to the Church, and the viceroy’s wife used her servants to abduct an unknown number of them and looked after them to prevent them falling into the hands of Satan, as would have happened if they had gone to ‘Moorish lands’.

Following their expulsion, the Moriscos from the village of Hornachos, an enclosed, warlike community, settled in and later took control of the corsair port of Sale, next to Rabat. In 1631 they negotiated with the King of Spain to hand over the town to him on several conditions, including that of the return of the children of whom they had been robbed. From kingdom to kingdom, village to village, there are many examples of communities where the youngest children were taken from the Moriscos.

As far as the exact number of Moriscos expelled from Spain is concerned, the figures quoted vary so widely it would be really unhelpful to name those authors who suggest one or other figure. Perhaps, following Dominguez and Vincent, the closest we can come is their total of approximately three hundred thousand. Moreover, most of the authors who have studied the Moriscos (Janer, Lea, Dominguez and Vincent, Caro Baroja...) speak of the killings that took place when those deported reached Barbary. Some of them affirm that almost a third of the Moriscos expelled from Valencia were killed on arrival. In this they are following Philip III's chronicler, Luis Cabrera de Cordoba, in his Relaciones de las cosas sucedidas en la corte de Espana desde 1599 hasta 1614: ‘and they (the Moriscos) are so horrified at the mistreatment and harm that the people of Valencia have received in Barbary, since a third of those who left have died, that very few of them wish to go there.’ King Philip, however, celebrated the operation and gave a gift of a hundred thousand ducats in Morisco possessions to the Duke of Lerma on the occasion of the royal adviser's wedding to the Countess of Valencia.

After the first expulsion, a series of edicts was issued that insisted on the deportation of any Moriscos who might have remained in Spain or returned there, permitting and even rewarding the murder or enslavement of anyone found. It should also be recognized that the expulsion edicts varied according to each kingdom, although basically these different orders varied only slightly. In the novel, I have used the first of these that was passed, in the kingdom of Valencia.

Among the exceptions, the city of Cordoba is particularly interesting. On 29 January 1610 the city council petitioned the King for permission to allow two old, childless harness-makers to stay in the city ‘for the general good and for the sake of the riders’. I have no evidence to suggest that apart from these two old Moriscos, who were to carry on looking after the horses, there were any other exceptions; nor do I know what His Majesty’s reply was to the request.

MORISCOS IN DON QUIXOTE TOP

Miguel de Cervantes' writings, such as Don Quixote and Conversation of the Two Dogs, offered interesting views of Moriscos. In the first part of Don Quixote, which takes place before the expulsion of 1609-10, a Morisco translates a found document containing the Arabic history that Cervantes is described as "publishing."

In the second part, after the expulsion, the character Ricote is a Morisco and a good mate of Sancho Panza. He cares more about money than religion, however, and thus leaves for Germany, returning later as a false Christian pilgrim with the purpose of recovering treasure that he has buried. He admits, however, that expulsion of the Moriscos is just. His daughter, María Félix, is brought to Berbery but suffers, since she is a sincere Christian.

WHAT WAS THE SIZE OF THE MORISCO POPULATION? TOP

(from ‘The

Muslim Expulsion from Spain’ by Roger Boase, ‘History Today’, Nov 2012)

There is much disagreement about the size of the Morisco population. The French demographer Henri Lapeyre estimated from census reports and embarkation lists that approximately 275,000 Spanish Moriscos emigrated in the years 1609-14, out of a total of 300,000. This conservative estimate is not consistent with many of the contemporary accounts that give a figure of 600,000. Bearing in mind that the total population of Spain at that time was only about seven and a half million, this must have constituted a serious deficit in terms of productive manpower and tax revenue. In the Kingdom of Valencia, which lost a third of its population, nearly half the villages were deserted in 1638.

There is equal disagreement about the number of Moriscos who perished in armed rebellion or on the journey into exile. Pedro Aznar Cardona, whose treatise justifying the expulsion was published in 1612, stated that between October 1609 and July 1611 over 50,000 died resisting expulsion, while over 60,000 died during their passage abroad either by land or sea or at the hands of their co-religionists after disembarking on the North African coast. If these figures are correct, then more than one in six of the Moorish population perished in the space of two years. Henry Charles Lea, drawing on many contemporary sources, puts the mortality figure at between two-thirds and three-quarters.

The demographic factor was one of the decisive arguments employed in favour of expulsion by Juan de Ribera in 1602. He warned Philip III that, unless he took swift action, Christian Spaniards would soon find themselves outnumbered by Muslims, as all Moriscos married and had large families, whereas a third or a quarter of all Christians remained celibate after taking holy orders or entering military service. The Moriscos, Ribera said, think only of reproducing and saving their skins, while their temperance in food and drink gives them a high life expectancy. Ribera’s fears were prompted by a census of the Valencian population that he himself had supervised that same year, which revealed that the Morisco population had increased by one-third.

OTHER "MORISCOS"

TOP

Morisco is sometimes applied to other historical crypto-Muslims, in places such

as Norman Sicily, ninth century Crete, and other areas, along the medieval Christian-Muslim

frontier.

In the racial classification of colonial Spanish America, morisco was used for a certain combination of European and African ancestry, regardless of religion, similar to the classification mulatto.

THE MORISCOS AND THE 21st CENTURY - ARE THE MUSLIMS TOP

UNASSIMABLE?

(From Moriscos and Jewish Converts: Religion as Cultural Identity Mercedes García-Arenal.

Professor and researcher, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Madrid

http://www.iemed.org/publicacions/quaderns/10/q10_209.pdf)

From the times of the expulsion itself there was ample debate over its rightness and legitimacy – people who had received the sacrament of baptism were being expelled to North Africa, that is, to Muslim territory – and this debate was taken up by historians in the 19th century. The bibliography on the Moriscos makes up a very abundant department of studies, one which has made and continues to make rivers of ink flow, the “Morisco river” referred to by the book of Bernard Vincent. 2 The Morisco question is an emotive one and has a strong capacity for connecting with contemporary problems. It can be seen, to some extent, as a live issue which it is not always easy to approach in a purely historiographical way. In modern times, there hovers over Morisco history the presence of Muslims in Europe, who are the target of intense reactions. Some of these reactions and their formulations in the Press today (whether Muslims can be Europeans or not, whether they are Muslims above all else, whether they are unassimilable, whether they are going to alter fundamentally the societies in which they settle, whether their religious beliefs are compatible with our cultural and political values, whether they feel a “civilisational hatred” for Europeans, etc.), although expressed in other terms, strikingly recall the discussions and emotions aroused in 16th-century Spain and settled with the expulsion of the early 17th century. Then as now, the discussion hinges, in reality, on the possibility or the desirability of assimilation. Is not assimilation, after all, an infiltration? The question, when all is said and done, is always the same: can they be us? The fundamental nature of this question is not changed by the fact that nowadays it is no longer good form to speak of assimilation, in the name of respect and of the freedom of different communities, or of a particular interpretation of the term “multiculturalism”. For frequently what is under discussion is the definition of our own identity and its construction; a question that is complex, sensitive and in perpetual evolution. Historical writing and the output of social sciences centred on the question of preserving identity are less given to studying the reverse question, i.e. the achievement of anonymity, of a total or partial non-differentiation that permits the disappearance (and therefore near-invisibility) in their surrounding society of hundreds of thousands of Moriscos, convert Jews... and European Muslims

Links

The Moriscos of Spain; Their Conversion and Expulsion -

Henry Charles Lea - 1901

- History - 318 pages Google Books

The Handless Maiden: Moriscos and the Politics of Religion in Early Modern Spain ... - Mary Elizabeth Perry - 2005 - 204 pages Google Books

http://www.iemed.org/publicacions/quaderns/10/q10_209.pdf

Moriscos and Jewish Converts: Religion as Cultural Identity Mercedes

García-Arenal.

Professor and researcher, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Madrid

References

Chejne, Anwar G. Islam and the West: The Moriscos, a Cultural and Social History. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1983. ISBN 0873956036.

Ehlers, Benjamin. Between Christians and Moriscos: Juan De Ribera and Religious Reform in Valencia, 1568-1614. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006. ISBN 9780801883224.

Harvey, L. P. Muslims in Spain, 1500 to 1614. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005. ISBN 9780226319636.

The Hand of Fatima, Ildefonso Falcones, Transworld Publishers, 2010

WHAT HAPPENED TO THE MUSLIMS (MORISCOS) AFTER THE SURRENDER OF GRANADA IN 1492 AND THEIR FORCIBLE CONVERSION TO CHRISTIANITY?

click to go to

WHAT WAS THE SIZE OF THE MORISCO POPULATION?

THE MORISCOS AND THE 21st CENTURY

|

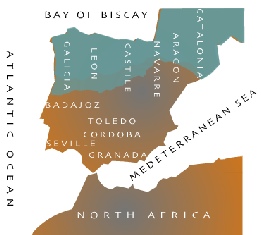

‘ The Reconquista’ (Reconquest) 711 - 1492 | |

|

|

|

|

| |