|

BARROS BASTO TV SPECIAL

A TV special on Captain Barros Basto was shown on Portuguese

national TV station RTP2

on Sunday, November 11, 2007 at 9.00a.m.

LAUNCH OF NEW BARROS BASTO BOOK,

THE PORTUGUESE DREYFUS, PORTO, SEPT 2, 2007

BARROS BASTO:

A MIRAGEM MARRANA DE ALEXANDRE TEIXEIRA MENDES,

por Puedro Sinde a seguir

by manuel lopes azevedo

from

http://www.friendsofmarranos.blogspot.com/

|

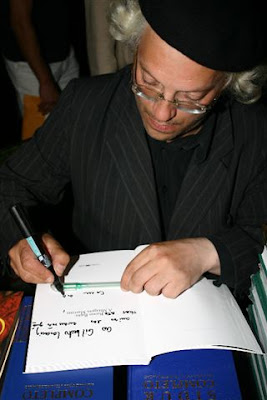

Author Alexandre Teixeira Mendes

signing copies at launch

(photo copyright by Monica Delicato) |

. manuel lopes

azevedo, Yaacov Gladstone,

Dr. Harold-Michal-Smith |

It was standing room only at the magnificent Kadoorie

Mekor Haim synagogue in Porto for the launch of a new

book on the life and work of Captain Barros Basto. The

book, by Marrano poet Alexander Teixeira Mendes offers a

new vision of the man and his times. Written in

Portuguese, (the English translation is underway), it is

entitled “Barros Basto, the Marrano Mirage”.

Barros Basto, a former Marrano himself, was a leader and

role model for thousands of Marranos hiding in the

villages of northern Portugal. He established the first

Yeshiva in Portugal, Rosh Pinah, since the forced

baptism of Jews in 1497. Captain Basto built the Mekor

Haim synagogue during the great depression (completed in

1938, the year 200 synagogues were destroyed in Europe)

as a spiritual haven to encourage Marranos to return to

their ancestral religion-Judaism.

The revival of open Judaism in Portugal was unacceptable

to the totalitarian Salazar government and the Catholic

Church. The captain was unjustly accused of homosexual

acts and stripped of his military rank and honour for

conducting circumcisions on returning Marranos. This was

a near fatal blow to the revival of the Marrano

movement. Those who came out fled back into hiding, many

losing their jobs and ostracized.

Captain Arthur Barros Basto was devastated and died a

broken hearted man in 1962. His granddaughter, Isabel

Barros Basto Lopes is supporting a campaign being

launched by the American and Portuguese Friends of

Marranos to clear his name. A petition seeking justice

for the captain will soon be launched.

The launch of Barros Basto, the Marrano Mirage, was made

possible by the generosity of Dr. Harold Michal-Smith

and Yaacov Gladstone, founder and president of the

American Friends of Marranos. They were both honoured

with a beautiful specially bound limited edition of the

book. Mr. Yaacov Gladstone announced a further donation

by the American Friends of Marranos to Ladina to support

the upcoming publication “Marrano Women in the

Inquisition” presently being researched by Fernanda

Guimaraes. It is hoped that the women portrayed will be

the subject of a play.

The book was presented by philosopher Pedro Sinde and

Yaacov Gladstone. Pedro advised the attentive audience

not to expect a traditional linear biographical story of

the Captain and his work of rescue amongst the thousands

of Marranos of northern Portugal. He resorted to a

metaphor of a tree to explain the book; Barros Basto is

the central trunk of the tree, surrounded by many

branches. Accordingly, the author may in fact be

describing biographical data, but then shifts to a

question concerning the oppression of the Catholic

church which in turn is linked to Salazar’s

dictatorship, and ultimately returns to the tree trunk

in a discussion of the oppression of the totalitarian

state on Barros Basto because of his democratic beliefs.

This rich narrative permits the reader to imagine Barros

Basto alive, accompanying him in his youth, during the

war, in the mysterious Oryamita Institute, in his work

of rescue, and in resisting the malicious connivance of

the “new state” and the Church. Contrary to most

authors, Alexandre transforms the object of his study

into his subject, making this a passionate book, not an

objective one.

Notably, this is the first time in Portuguese

literature, (and this book IS literature, a book within

a book with its one hundred and sixty or so lengthy

footnotes), that a different concept of Portuguese

identity is discussed openly. Following theories

developed by Teixeira Pascoais, leader of the Portuguese

Renaissance movement at the turn of the 20th century and

of Antonio Telmo’s thesis of the secret history of

Portugal (Professor Telmo, himself a Marrano, wrote the

preface to the book), the author describes the

Portuguese psyche as essentially Jewish, a golden thread

of Portuguese literature revealed in Sampaio Bruno (the

“Covered One” in the 19th century, Fernando Pessoa (the

“Message”) in the 20th century, Camões in the epic

Lusiadas and Bernardino Ribeiro in “Menina e Moça” in

the 16th century, the latter published at the same

Jewish printing house in Ferrara that published Samuel

Usque’s “Consolation for the Tribulations of Israel” and

the Ferrara bible dedicated to Dona Gracia.

A beaming and visibly moved Yaacov Gladstone said how

proud he and Dr. Harold Michal-Smith were for helping to

make Alexandre’s dream come true. They had met Alexandre

four years previously when the book was only a dream.

Yaacov expressed the hope that other organizations such

as the American Sephardic Federation, The Joint

Distribution Committee, Jewish Federations, etc., will

understand the urgency of continuing the work of Barros

Basto to bring Jewish education to the Marranos or they

will disappear like the Chinese Jews of Kaifeng.

The American and Portuguese Friends of Marranos are

determined to help Marranos, wherever they may be, to

regain their Jewish identity. Readers who wish to

participate in this great mitzvah of bringing Jewish

education to the Marranos can make cheques payable to

“El Centro de Estudios Judios” and mail it to American

Friends of Marranos, 310 Lexington Avenue, Ste. 5D, New

York, New York, 10016 or email Yaacov at

yanklegladstone@aol.com

|

CAPTAIN BARROS BASTO,

THE APOSTLE OF THE MARRANOS

by Inacio Steinhardt

http://www.saudades.org/barrosapos.html

|

"Barros

Basto is a legend about whom a biography is waiting to be

written.

But the life of a devout Jew

with a cause that failed is hardly

the stuff of best-sellers." |

The above quotation from Elaine and Robert

Rosenthal's article "The Portuguese Dreyfus" was chosen by the authors

to open the book "Ben-Rosh ---- A Biography of Captain Barros Basto,

'The

Apostle of the Marranos".

Did Barros Basto's cause really fail? and

why?

Barros Basto, as a person, had a bitter end.

He was dismissed from the army and dishonoured and his yeshiva was

closed. Political enemies, and the hatred of the catholic clergy who

felt threatened by him, combined to take advantage of internal

dissensions among the Jews, and destroy him as a person.

Yet, those Jews who opposed Barros Basto's

work were convinced of their own righteousness, and each of them was

sure of acting in the best interests of the Jewish faith and of the

marranos. Were they right? It is important to be sure of this, lest the

same mistakes be repeated in our days.

Barros Basto was by nature a man of

principle and of action, devoted to the betterment of the world and of

humanity. He was one of the founders of scouting in Portugal; he fought

alongside, and worked with, the republicans who overthrew the monarchy;

he even founded a new religion - Oryam - in an attempt to mould the

character and the way of life of the "mountaineers" of his birthplace.

From his loving grandfather he learned the

secret of his family’s Jewish origin. This revelation led him to try to

force his way into the mainstream of Judaism, despite the opposition of

the Jewish community in his country.

His ancestors were "New Christians",

descendants of those Jews who had been forcibly converted to

Christianity in 1497. But they were not necessarily crypto-Jews or

marranos . The moment he returned to Oporto and began to form a Jewish

community with the few Ashkenazi residents of the town, he was surprised

at the number of his compatriots who appeared before him and admitted

having practiced Jewish rites in secret.

Fascinated with these revelations, Barros

Basto travelled extensively through the villages and towns of northern

Portugal, in order to get acquainted with these crypto-Jews, and to

learn more about their religious practices and their way of life.

He made no attempt to change such beliefs

and practices. What he did do was devote himself to stripping the

secrecy from their way of life, to convincing them that the Republican

revolution - in which he had taken part - had opened a new era of

freedom for the still practicing descendants of the Jewish victims of

forced conversion. Unfortunately, he did not know then just how

shortlived this freedom was to be.

Barros Basto’s "Work of Redemption" was

intended to lead the marranos into practicing their own version of the

Jewish religion openly and without fear, and to help them, by all

available means, to recover and bring up to date all the information

about Judaism which they had lost during the preceding four centuries.

The "Portuguese Marranos Committee" of

London, which was formed as soon as the news of the discovery of secret

Jews in Portugal became known in the Jewish World, approved Barros

Basto’s work and gave it financial support.

Not so Maurits Van Son, of Amsterdam, and

his "Nederlandsche Pro-Marrano Vereeniging".

In his booklet "Verleden en heden der

Marranen in Portugal" , Van Son, an orthodox Jew, wrote: "... They don’t

ask for anything, but their eyes speak for their will to be admitted

into the assembly of Israel."

They did not ask for anything, it’s true.

They don’t ask for anything even today. Their faith, and their belief,

were strong enough to keep them Jews - even in the eyes of their

Catholic neighbours - for 400 years. Why then should they need to ask to

be admitted? They believed in the Captain; they were ready to take the

hand that he extended to them, and eager to learn what he was teaching

them - the history of their people and their own history, the meaning of

their own Judaic traditions, and the comparable practices of the rest of

the Jewish World. By no means, however, were they ready to give up the

faith and the practices which they had learned from their grandmothers.

Manuel Marques, a one-time Catholic priest

who has since left the priesthood to return to secular life, had this to

say about the faith of the marranos: "I have changed, because everything

has changed around me.

It was the contact at the moment of death

that impressed me the most. I felt their faith to be so strong that I

could almost touch it. This became a big problem for me: I had come to

Belmonte in order to convert the Jews , to carry on the work of my

predecessors, but they were the ones who converted me."

Rabbi Baruch Ben-Jacob, a "haham" from

Salonica, whom the Dutch committee hoped to appoint as Chief Rabbi of

the marranos, decided to decline the position, because he could not go

along with the Captain’s views, nor with the attachment of the marranos

to their traditions.

On his departure, after he had told them

that old traditions would have to be abandoned and replaced by orthodox

practices, the old women of Bragança wondered "is Judaism a religion of

what to eat and drink and such material things?".

Yet Rabbi Ben-Jacob, in his report spoke of

his emotion: "I could not hold back the hot tears in my eyes. Thus

amidst a great enthusiasm of faith and religion, I departed sorrowfully

from such an impressive assembly".

The Jewish community of Lisbon had mixed

feelings about the discovery of the marranos. No Jewish heart could

remain unmoved, in the face of the phenomenon of people who were strong

enough to keep their Jewish faith for over 400 years. Some of the Jews

of Lisbon were in favour of accepting the marranos as they were; others

claimed that the marranos had already become "alien corn", and that any

contact with them would endanger the precarious status of the small

Jewish community of Portugal, which was itself seen as alien by the

authorities. Finally, there were those among the leaders of the

community who, after consulting the chief rabbi of Eretz Yisrael,

were willing to accept the marranos as brethren, provided only that

these would undertake to observe orthodox practices, and accept the

hegemony of the Lisbon community.

Under severe pressure as a result of the

problems created in his army service by religious enemies, the Captain

committed several grave mistakes in the management of the Community

which he led, and allowed personal feuds and jealousies to develop and

flourish among those persons whom he selected to replace him in his

work, during his absences.

The first anonymous denunciation to the

police was seen by the latter as an internal community matter, "the Jews

washing their dirty linen".

Nevertheless it was the first skirmish in

the long campaign of civil and military persecution against Barros Basto,

which in the end was to destroy him physically, though never in spirit.

The repercussions of the persecutions

against the captain, the closure of the yeshiva, the the freedom of

religion.

Growing strength of the reactionaries in the

Roman Catholic Church and of the political police, and last but not

least, the rise of Nazism in Germany, all worked together to frighten

those marranos who had believed the Captain, and who had prematurely

celebrated the freedom of religion.

The return to clandestine Jewish worship was

very hard, especially for the younger generation. In townlets and

villages, which when Barros Basto first arrived counted hundreds of

practicing crypto-Jews, there remain today only a few individuals,

sometimes only pointed out as "Jews" but ignorant of any Jewish

tradition. From time to time a son or a daughter of such a family finds

his or her way to full conversion, and seeks a place in mainstream

Judaism.

But there is no easy path from a secretive

marrano home to the Synagogue with all its internal divisions.

Traditionally, Judaism is not a religion of proselytism. Seldom are

newcomers received with love and open arms. Judaism is an ethnic

religion, and the Orthodox rabbis are usually suspicious of those who

tap at their doors. The marranos themselves are also cautious and

suspicious. These new searchers suffer, and resent the cold welcome

which they usually receive.

Nevertheless, there do exist examples of a

successful relationship, eventually leading to full integration. The

crypto-Jewish community of Belmonte has succeeded in surviving the

crisis. It is the only such community in Portugal to have done so.

Perhaps because the influence of Barros

Basto in Belmonte was less strongly felt (although some young men of

Belmonte attended the Yeshiva in Oporto, and never returned home...),

perhaps because of some sort of a feud that existed between Barros Basto

and Samuel Schwarz, the "discoverer" of the Belmonte community, perhaps

because Belmonte has been widely publicized by Schwarz and several other

visitors - the crypto-Jews of Belmonte were eventually offered full

integration into the mainstream of Judaism.

Twenty years ago, the present Catholic

priest of Belmonte claimed in a letter to this author that he personally

was against giving Catholic sacraments to people who, as an open secret,

kept the Mosaic law at home.

"Somebody should come from Israel to

convince them that now they are free to practice their religion in

public. Let them build a synagogue and I will be the first to help."

Father Registo’s wish became true. A

synagogue was built in Belmonte’s old Jewish quarter, "Marrocos."

Two factors have influenced the acceptance

of the change by the Belmontese marranos: the much wider choice of

marriage partners which followed the end of endogamy within the strict

family clan (this was already causing serious health problems) and the

end of religious matriarchy.

This article is being written shortly before

the presentation to the public of the biography of Arthur Carlos de

Barros Basto at the Kadoory Mekor Haim Synagogue, in Oporto, which he

himself proudly inaugurated in 1938, after all his years of trouble.

The synagogue was closed for many years, but

has reopened now for the benefit of a community of newcomers. Marranos

are seldom seen there.

One year earlier, on December 5th.1996 (the

date on which, 500 years previously, the Edict of Expulsion was signed

by king Manuel I), a synagogue - Bet Eliahu - was inaugurated in

Belmonte.

Most of the Belmonte community have

converted to Judaism. But is that the appropriate verb to use?

"Converted"? People whom even the priests themselves, let alone the rest

of the population, called by no other name than "judeus" (Jews)? Did

they need to be "converted"?

They now pray in Hebrew; men wear talitoth

and tephilin, women go in the streets of Belmonte with fancy hats no

different than in Bnei Brak and Mea Shearim.

However, in the secrecy of their homes, they

still light the same traditional shabbat oil lamps, and bake their own

matsot..... after being for so many years "crypto-Jews", hiding their

religious acts from the eyes of the priests, they have become "crypto-marranos",

hiding their marrano activities from the rabbis.

Is there any reason for Orthodox mainstream

Judaism to claim exclusive proprietorship of the Jewish faith? Should

not such communities as the Falasha (Ethiopian), Ben Yisrael (India),

the Marranos and any other bona-fide Jewish groups (including

Conservative and Reform Jews) be considered equal members --- different,

perhaps, but equal nonetheless --- of the same religion?

Naturally those who choose orthodox Judaism

should be accepted according to the rules of Halakhah. Their motives

might be the absence of solid traditions in their families, or even the

wish to marry a member of a different Jewish group. But otherwise, why

should they need anybody’s approval to be what their forefathers taught

them to be?

Barros Basto’s biography is witness to the

difficulty of freeing oneself from the stigma, when one is descended

from Jews.

Inacio Steinhardt

January 1998

Copyright 1997, 1998, 1999 Inacio Steinhardt

|

|

|

|

Portal to a

Portuguese Past

Captain Arturo Carlos

de Barros Basto (the 'apostle of the Marranos)

The Jerusalem

Post,

December 13, 2002

Michael Freund,

Director of Amishav

Nestled along the

right bank of the Douro River in northern Portugal, the city of Oporto

seems an unlikely setting for one of the more intriguing, if lesser

known, dramas of 20th century Jewish history.

With its wide avenues, bustling port and increasingly profitable wine

industry, Oporto strikes the first-time visitor as a typical European

commercial hub, one in which medieval monuments and imposing cathedrals

stand within just a few blocks of modern office buildings and rows of

banks and other financial institutions.

And yet, down a small, unassuming street called Rua de Guerra Junqueiro,

stands a majestic synagogue called Mekor Haim (“Source of Life”) which,

some 70 years ago, was the focal point of an extraordinary, if brief,

revival of Jewish life among thousands of the region’s anousim (Hebrew

for "those who were coerced," as many Marranos prefer to be called).

The nascent movement to return to Judaism was led by none other than a

decorated Portuguese Army officer, Captain Arturo Carlos de Barros Basto,

who served his country faithfully in the First World War. And while his

determined efforts to spearhead a mass return to Judaism were ultimately

suppressed by the authorities, they continue to capture the imagination

of Jews and non-Jews alike.

Born in a village near Oporto in 1887, Barros Basto was a descendant of

anousim, and he grew up with vague memories of his grandparents secretly

lighting candles on Friday nights and observing other Jewish rituals.

“There does not seem to be any doubt that his grandfather knew of his

family´s Jewish origins… and that he transmitted this knowledge to his

grandson,” notes Inacio Steinhardt, Tel Aviv correspondent for the

Portuguese News Agency and co-author of a 1997 biography of Barros Basto.

At an early age, says Steinhardt, Barros Basto had a tendency “to abhor

certain facets” of the Catholicism he was raised with, “and to idealize

a more sublime relationship with the Creator.”

In 1916, while fighting on the European front, Barros Basto commanded an

infantry squadron and saw action in Flanders, where he even survived a

gas attack. There, according to historian Howard M. Sachar, Barros Basto

had an experience that would prove to be a turning point in his life.

One Friday evening, he ambled into the tent of a French liaison officer

who happened to be Jewish. When he saw the officer lighting candles, the

Frenchman explained that it was a “Jewish Sabbath tradition”. For Barros

Basto, writes Sachar in his book Farewell Espana: The World of the

Sephardim Remembered, “the dim memory of his grandparents’ ritual

suddenly locked into focus.” He returned to Portugal a changed man.

Determined to undergo formal conversion to Judaism, Barros Basto

overcame numerous obstacles and made his way to Spanish Morocco, where

he fulfilled his goal and returned to the faith of his ancestors under

the guidance of the rabbinate in Tetuan.

With a newfound zeal, Barros Basto returned to Oporto, married a Jewish

woman, and set about the task of encouraging his fellow crypto-Jews to

come out of the closet and openly return to the Jewish people. He

established a synagogue and started a weekly newspaper, HaLapid, in

which he wrote under his Hebrew name of Abraham Ben Rosh.

Dressed in his military uniform, Barros Basto began visiting remote

areas throughout northern Portugal, pleading with the anousim to embrace

Judaism. “He initiated a process of welcoming the crypto-Jews and their

descendants back to Judaism”, says Rufina Bernardetti Silva Mausenbaum,

a writer and descendant of Portuguese anousim. “He travelled to the

villages and towns to reassure these frightened people that it was safe

at last to openly practice Judaism once more… of these trips were made

with two medical doctors accompanying him to perform circumcisions when

required”.

As a result of these efforts, Barros Basto quickly became known as the

“Apostle of the Marranos”, and within a few years his efforts began to

bear fruit when the Mekor Haim synagogue in Oporto was formally

dedicated. The building, which was donated by Elie Kadoorie, and built

on land that had been purchased by Baron Edmond de Rothschild of Paris,

came to serve as a kind of headquarters for Barros Basto’s movement to

restore the anousim to the Jewish people.

Recognizing the importance of education, Barros Basto succeeded in

establishing a yeshiva on the synagogue’s premises, which he called Rosh

Pina, Hebrew for “cornerstone”. The school operated for nine years,

during which it trained some 90 students in subjects ranging from Hebrew

to Jewish history and tradition.

All these activities, however, did not go unnoticed by the church and

the authorities, neither of whom looked too kindly on Barros Basto’s

efforts, particularly when thousands of people began to respond to his

call to return to Judaism.

“Anti-Semitism was rampant in Europe during the `30s, working against

his efforts and dreams,” says Mausenbaum. “This wave of anti-Semitism

swept through Portugal as well, affecting the resurgence of Jewish life

he had sparked, which was viewed with severe criticism by the Church and

the new regime headed by Antonio Salazar [the authoritarian Portuguese

premier who ruled from 1932 to 1968 - MF].”

In 1935, a local Oporto priest named Tomaz Correia da Luz Almeida set in

motion a series of events that would ultimately lead to Barros Basto’s

dismissal from the army and the disintegration of the burgeoning

movement he had founded.

Anxious to stem the tide of those abandoning Catholicism to return to

Judaism, Almeida brought trumped up charges against Barros Basto to the

police, alleging that he was a “degenerate” who engaged in homosexual

acts with his students. The Oporto prosecutor brought charges against

Barros Basto, leading the Portuguese Army to initiate court-martial

proceedings against him. After dragging on for over two years, the case

was finally dropped in 1937 for lack of evidence.

But, as historian Sachar puts it, “the damage was done. By the

mid-1930s, parents had withdrawn their children from the Rosh Pina

school, and Barros Basto had become persona non grata among his

once-devoted marrano followers.” In 1943, the Portuguese Ministry of

Defense, citing unspecified reasons of “good and welfare”, revoked

Barros Basto’s commission as an officer and summarily drummed him out of

the service, leading historians to dub him the “Portuguese Dreyfus”

(after the French general staff officer Alfred Dreyfus, who was wrongly

accused and convicted of treason in 1894).

The thousands of anousim whom Barros Basto had inspired to investigate

their Jewish ancestry and heritage quickly got the message: it was not

yet safe to return to Judaism. And then, almost as quickly as it had

begun, the movement Barros Basto initiated rapidly faded away.

Climbing the stairs to the Mekor Haim synagogue’s top floor, I proceed

down a hallway and enter the library. Lining the shelves are a variety

of religious books, many of them dusty and torn, signifying both their

age and the ample use to which they were once put. Impulsively, I open a

cabinet on the wall, where I discover a pile of old booklets in

Portuguese, carefully bound and wrapped as if awaiting distribution.

“Catecismo Israelita” (The Belief System of Israel), a 59-page volume,

discusses the mission of the Jewish people in this world as well as

various aspects of Jewish philosophy and practice. “Judeus & Proselitos”

(Jews and Converts), explains in 45 pages the meaning of conversion and

Jewish attitudes toward converts throughout the ages. Both booklets

proudly bear the name of “A.C. de Barros Basto” on their cover, and

state that they are publications of Yeshivah Rosh-Pinah, the school he

worked so hard to establish.

Leaving the room, I proceed to the women’s balcony, which overlooks the

main sanctuary where untold numbers of Portuguese anousim, undoubtedly

led by Barros Basto himself, once gathered to offer prayers just as

their ancestors had done before them. The interior of the synagogue is

strikingly beautiful, yet the silence in the room is as piercing as it

is anguished.

“The synagogue may be empty, but you can feel the voices of the

worshippers who once prayed here,” says Rabbi Eliyahu Birnbaum, the

former Chief Rabbi of Uruguay who accompanied me on the visit. “Though

the library and beit midrash are no longer in use, you can still feel

and hear the students who once sat here, learning Torah and grappling

with the age-old question of what it means to be a Jew,” he tells me.

And yet, I remain troubled. Here, for a few brief years some seven

decades ago, an abrupt awakening had taken place. Thousands of

Portuguese men and women whose ancestors had been coerced into adopting

Christianity five hundred years ago, suddenly stepped out of hiding and

sought to reclaim what had been taken from them by force. Could it be, I

thought, that the Pintele Yid, the Jewish spark, had survived in

Portugal for all those centuries only to come alive briefly in the

1930’s and then be snuffed out in a spasm of intolerance by Barros

Basto’s persecutors?

No, Rufina Mausenbaum later reassured me, Barros Basto’s accomplishment

was not short-lived. “Though he never quite succeeded in reviving the

full potential of Portuguese Judaism in his time,” she said, “I believe

he gave hope and strength and helped nurture the Jewish soul of the

secret-Jewish communities of Portugal.”

Today, she notes, Portugal´s young anousim look to Barros Basto as an

inspiration, “speaking openly and wishing for their own ‘Ben Rosh’, as

he was known, to assist them in their return”.

Indeed, Barros Basto biographer Inacio Steinhardt says that most of the

current congregation’s few dozen members are “people that found their

Jewish roots and returned to Judaism or are in the process of

returning.” An ambitious effort by the synagogue’s dynamic Israeli-born

president, Moshe Medina, he notes, aims at drawing in local anousim,

welcoming them into the community and educating them about Judaism.

Medina’s brother, Marco, confirms that a rebirth, of sorts, is underway.

Just recently, he relates, he was sitting at a café in Oporto reading a

book in Hebrew. A young Portuguese man came over and asked him what

language he was reading. “When I told him, he got all excited because he

was from the anousim,” says Medina. “He said to me, ‘I love Israel and I

love the Jewish people – my people’. So I invited him to come to the

synagogue, to learn more about his heritage.”

“I get calls every week from Portuguese Marranos seeking a connection

with Judaism,” Medina says. “They want to learn more, celebrate the

holidays, and become Jews. There are hundreds and hundreds of anousim in

this area, and we need to reach out to them.”

It seems, then, that Rufina Mausenbaum was right, after all. Decades

later, Barros Basto’s efforts continue to reverberate among Oporto’s

hidden Jews. “His dreams and his deeds,” she told me, “were

indestructible”.

And so, it appears, is the tenacity of the Jewish soul, which, against

all odds, is struggling to reemerge in places such as Oporto.

And while they may face an uphill battle, Portugal’s anousim can at

least find solace in the fact that although their commanding officer,

Captain Arturo Carlos de Barros Basto, is no more, his dream and his

spirit live on.

|

|